Novruz Bayramy

Novruz is associated

with spring, start of agricultural activities, renewal of nature and warm days. This

period being of great importance it caused many traditions and rites associated with

magic, the cult of nature and earth, and belief in the perishing and reviving nature etc. Virtually, celebrations began four weeks before the actual day of festivity.

These four weeks - or, exactly four Wednesdays - were each devoted to one of the four

elements and called correspondingly, although names varied from location to location. They

were: Su Charhshanba (Water Wednesday), Odlu Charhshanba (Flame Wednesday), Torpaq

Charhshanba (Earth Wednesday), Akhir Charhshanba (Last Wednesday). According to folk

beliefs, on Water Wednesday 'water renewed and dead-water came to stir'; the Flame

Wednesday was believed the day of fire rebirth; on Earth Wednesday the earth revived. On

the Last Wednesday the wind opened tree buds and spring arrived.

Another interesting version of the "four Wednesdays" existed in Shirvan area of

Azerbaijan. They were devoted: the first Wednesday to air, the second one - to water, the

third to the earth, and the fourth one - to trees (plants). It meant: on first Wednesday

air warms, water on the second, the third week means the earth to wake, the fourth one

stands for trees and plants to revivify.

The most important of the

Wednesdays was the Akhir Charhshanba (Last Wednesday before the vernal equinox) and most

of important rites and ceremonies were delivered that day which concerned all the aspects

of human life. Those rites were intended to provide welfare for an individual, his family

and the community in general, to get rid of the old year's troubles and to avert a

calamity.

The most important of the

Wednesdays was the Akhir Charhshanba (Last Wednesday before the vernal equinox) and most

of important rites and ceremonies were delivered that day which concerned all the aspects

of human life. Those rites were intended to provide welfare for an individual, his family

and the community in general, to get rid of the old year's troubles and to avert a

calamity.

First of these essential traditions was the concoction of a ritual food named Samani

(malt) which epitomized fertility of nature and the human race. This food had magical and

cultic importance and was considered sacred ritual food. For instance, Samani was used to

cure infertile women: a dish with sprung wheat for Samani was put on the head of a woman;

another woman poured a little water into the dish cutting the squirt with scissors and

pattered: "Oh, the Power which fecundated this (samani), fecundate this woman."

The process of concoction of Samani was arranged as a religious ritual with only women

admitted. The fire under a Samani kettle was put by "bashi butov gadin" (the

happiest woman of the community) but the entire ceremony was leaded by

"agbirchek" (the most respected woman). The place of the ceremony was closed for

males, those adherent for different faith and "evil-eyed" women. In some regions

Samani was prepared adding a pinch of salt to preserve it from the evil-eye. The entire

ceremony of concoction was called "Samani toyu" (Samani feast) and was

accompanied with ritual dancing and singing.

As to Samani rite's

origin, it is considered to associate both with symbolizing the renewal of nature and the

cult of plants. The latter is also can be well illustrated with the following rite called

"Bailment of Trees" which was delivered on Akhir Charshanba: a male with an axe

approached an unfertile tree as if intending to chop it down. Another person came up and

asked about the reason of his intention and got the answer that the tree did not fruit.

Then, his companion talked him not to chop the tree and bailed it out till next year. The

same way all unfructiferous trees were "bailed out" and none of them was chopped

down.

Other very interesting traditions were associated with water and fire. As to water, its

natural feature to wash the dirt away inhered its function as a means of circumcision and

cleanup. Among such rites was jumping over a stream to purify from the sins of the year

past. Another rite consisted of family members besprinkling each other before going to bed

on Last Wednesday.

Azerbaijan as a cradle of fire-worshipping had rich Novruz traditions associated with fire

which also was believed a way to purify oneself. Making fires on streets, roofs and

elevated points was wide accepted and jumping over a fire on Last Wednesday was considered

compulsory for community members regardless to their age and sex. In Azerbaijan it was

accepted to jump either once over seven fire piles or jump seven times over the same one.

In ancient times the fire was put by an underaged boy using flint and this fire was

believed to be pure.

To pass to the actual day of

Novruz, vernal equinox was proclaimed to have come with flares and gun shooting.

Traditionally, all family members had to stay at home this day, paying no visits and

accepting no guests. They said: "The one that is out on the holiday eve will spend

seven years in wandering".

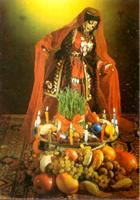

All days that preceded the holiday were given to profound home-cleaning and concoction of holiday food, which had its own traditions. For instance, it should have include components usually not used. Here the magic "7" has to be mentioned as an element often found in Novruz rites, among which "Yeddi lovun" (seven things) is remarkable. Actually, it consisted of putting seven things - salt, bread, an egg, rue, a piece of coal and a mirror - in a copper tray onto the holiday table and leaving them for 12 days. Conceivably, this tray and things were a sort of gift to the sun.

According to beliefs, plenty of food and holiday dishes would

provide sufficiency of these products in New Year. Some kinds of ritual food had magic

meaning - like eggs which were believed to bear nucleus of new life.

Usually, traditional Azeri plov of several sorts, sweat

cookies and fruits were essential elements of holiday table, although there are variations

according to territorial affiliation.

Nowadays, most of the above traditions are preserved in Azerbaijan, although differing

from region to region. As to Baku, below I provide an extract from "The Old

Baku" by Husseingulu Sarabski which tells a fairy tail of Novruz in Baku.

Novruz was celebrated in Baku much more opulently than other holidays. They began preparation long before. Every Tuesday they build fires in courtyards and at gates. Women burned rue with words of spell to avert all troubles and calamities. Many Baku men were fishermen and their mothers, wives and children added while spelling:

Die away, gilavar, haul, hazri,

My father (or son, or husband) to come home

The lesser time was left till the holiday, the more cheery

became the city. Grocers decorated their shops with mirrors, drawings from Firdowsi's

"Shahnameh" and paper lanterns. They hung a bell at the shops' doors and rang

them aloud to extol their wares.

Children amused grown-up with games and got sweat cookies in reward. Another way to get

dainties was "sallama". Houses in old Baku were mainly one-storied and were easy

to climb. Children (and not only) tied a pouch to a rope and downed it into a chimney.

They never took it back empty cause hosts always put something in.

On the holiday eve all the family gather together. The head of the family, busy with namaz

and prayers, still does not touch the holiday food on the tapis and no one can do that

without his permission. At this particular time his elder sons rushes into the room and

tells that a gunshot announced the holiday has arrived. Father takes his watch out of the

pocket, opens the case and says that there are several minutes left. Then he sits down at

the tapis and tastes the holiday melon. The hostess brings in milk plov and serves

everybody, after which they cleared away the dinner-things.

Open doors of houses told that the host was at home and the house is ready for receive

visitors. On the carpet in the sitting room they served a treat of sweat cokkies -

sheker-burah, sheker-churek, pakhlava, nogul, pistachios, dried sycamine fruits, raisins,

nuts, apples, oranges, etc.

The quests were greeted either by the elder son or a nephew of the host. They sprinkled

the quests' hands with rosewater and ushered them in. A quest was immediately served tea,

traditionally made with additions of cardamom, canella and ginger.

Such visits were paid three days after Novruz. Then women had their celebrations for a

week.